In my guise as a magistrate I have become familiar with a thrilling document called the “Magistrates’ Court Sentencing Guidelines”. It’s an entirely public, well, publication, as justice is meant to be transparent and accessible to all. And if you search for “theft” in the guidelines, you will find a variety of flavours, including “theft of a pedal bicycle” (an offence we try quite often here in Cambridge) and “theft in breach of trust”. It has its own offence because the idea of someone doing something wrong while operating in a position of trust or responsibility is seen as particularly serious. And in recent months we have seen something of a rash of people engaging in money laundering while working in a job which is supposed to involve a measure of anti-money laundering activity. On 7 May 2019, for instance, the National Crime Agency announced the jailing of three men – two bankers and an accountant – who had colluded to steal money from the bankers’ customers and launder it through accounts set up by the accountant. In total they stole £390,000, mainly from elderly customers – and were jailed for fraud by abuse of position and money laundering.

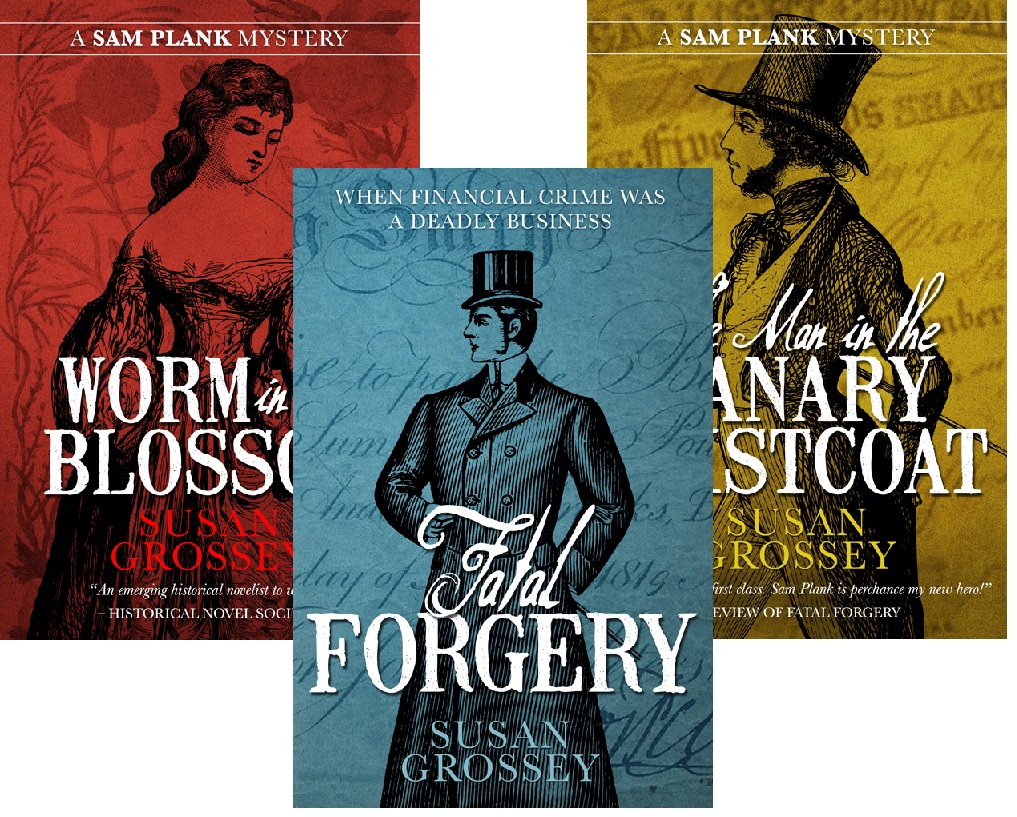

This is a particularly difficult risk for the MLRO to manage. Of course we try to ensure, through pre-employment screening, that only honest and capable people are employed within the regulated sector; we do criminal records checks and we take up references. For the most part this makes it harder for those who are dodgy from the outset – those who want a job in the regulated sector simply so that they can launder money – to get in. But what of those who start out with good intentions and end up going astray? People fall from the path of righteousness for all sorts of reasons, from genuine need to simple greed (now there’s a title for a novel – © Susan Grossey 2019). And to guard against these situations, the MLRO’s best defence is a long nose and at least one big ear.

The long nose is for snooping around, in the most benign fashion. Does an employee start turning up for work in a car that is out of his price range (given his salary), or talking about holidays that are beyond her financial reach? (There may be another source of wealth… but there may not.) Conversely, does a member of staff seem more agitated or stressed than usual, or more unkempt? Displaying behaviour that could suggest mental anguish or money worries? The big ear is for listening to concerns before the employee takes matters into their own hands and decides that the only way to get the money to pay off a debt or escape an abusive relationship or live the dream lifestyle is to turn to crime. Organised crime gangs have long noses and big ears of their own, to sniff out weaknesses and listen to gossip, in order to get their hooks into those on the inside who can do the dirty laundering for them. They know that money laundering is a people business, and the smart MLRO remembers that too.